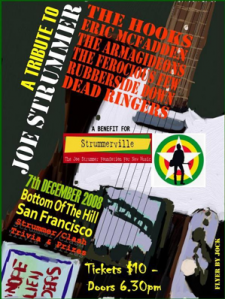

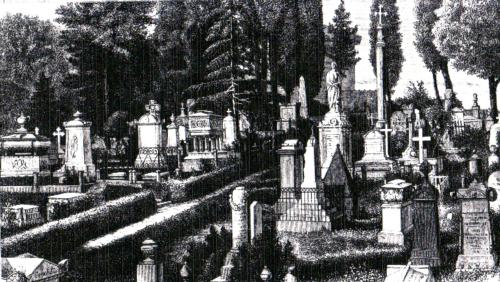

New England Abolitionists Buried in Florence, Italy

In October I gave a paper at a really interesting conference in Florence having to do with the English Cemetery. At least 80 Americans were also buried there in the 19th-century, including Theodore Parker. I spoke on Edmonia Lewis who began her life in Italy in Florence – – and said a bit as well about Sarah Parker Remond who was born in Salem and studied medicine in Florence (I should be clear that neither woman is buried there; they were part of the larger Florentine ex-pat community.)

The restoration of the English Cemetery is under the direction of the extraordinary scholar and activist, Julia Bolton Holloway. Photographs are from her websites.

For some of the conference papers and much more info. Google: City and The Book V

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s tomb

Theodore Parker’s original grave. A more elaborate monument was installed later.

Theodore Parker’s original grave. A more elaborate monument was installed later.

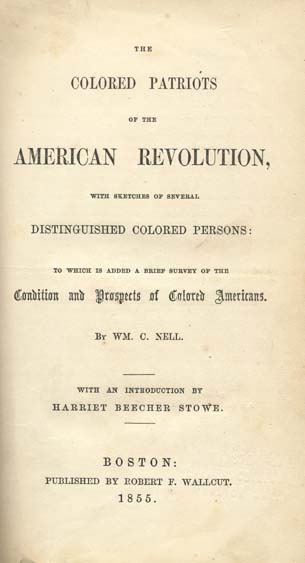

In April of 1855, Boston was abuzz with talk about a controversial court case. The Reverend Theodore Parker, whom friends and co-workers called “Minister to the Fugitive Slave,” was to stand trial for inciting a riot.

The previous spring, Parker had addressed an abolitionist crowd gathered at Faneuil Hall. He urged them to take action to prevent a fugitive slave from being returned to his master. A riot did, in fact, follow Parker’s speech, and he was charged with inciting it. Now, a year later, the case had come to trial.

Parker defended himself by attacking the immorality of slaveholders and all those who helped protect “the peculiar institution.” In the 200-page defense he wrote and later published, he equated morality with active, even if illegal, opposition to slavery.

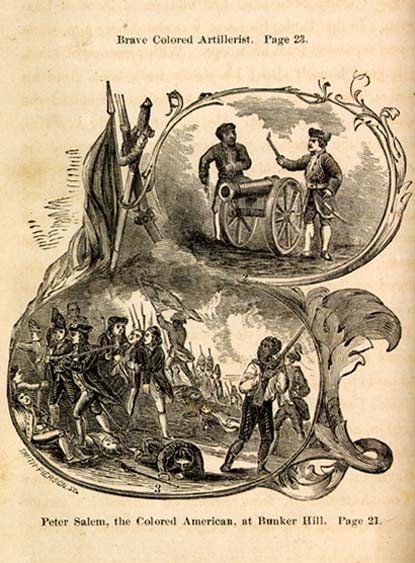

He drew upon the story — well-known in Boston — of a young couple who had, like many fugitive slaves, been his parishioners. William and Ellen Craft had made a 1,000-mile escape from slavery only to find themselves in danger in Boston. When slave-catchers came to reclaim them, Parker and other abolitionists defied the law and risked arrest to protect the couple.

The Crafts’ story was compelling indeed. Both of them were born into slavery in Georgia. William’s first owner was a gambler, who sold off his slaves one by one to pay his debts. When his master decided that a slave with a marketable skill would bring a higher price, he apprenticed William to a carpenter.

Ellen was the daughter of a slave named Maria and Maria’s master, Colonel James Smith. Bitterly resentful of the fact that the light-skinned Ellen was often mistaken for a member of the family, Mrs. Smith gave the 11-year-old girl to one of her daughters as a wedding present.

Ellen and William met in Macon, Georgia, in the early 1840s and fell in love. William described their condition as “not by any means the worst”; still, they despaired at the thought of spending their lives in bondage. Knowing that as long as she was a slave, her children would be born into slavery, Ellen resolved never to marry and have children. “But after puzzling our brains for year,” William recalled, “we were reluctantly driven to the sad conclusion that it was almost impossible to escape.” They decided to get the consent of their owners and were married in 1846.

Almost three years passed before the couple devised an ingenious and audacious plan. Ellen was so light-skinned that she could pass for white. They agreed that she would disguise herself as a young white man traveling north attended by his slave. William used his savings to purchase the clothing and accessories that Ellen needed. She would cut her hair, don clothes befitting a gentleman, and wear dark glasses. At the last minute, they realized that Ellen would have to sign the guest register at their lodgings; it was illegal for slaves to learn to read or write, so they decided to bind her arm in bandages and say that they were going north to seek medical treatment. With an injured arm, she could ask others to sign for her without arousing suspicion.

On December 21, 1848, they slipped out of Macon. For four harrowing days, they traveled by train, boat, and stagecoach. Their ruse was nearly uncovered several times when fellow travelers or stationmasters questioned why a man would risk taking a slave to Philadelphia where he could so easily run away. William served his “master” with such devotion that Ellen could respond convincingly that she had little fear of that. Luck was on their side, and they arrived in Philadelphia on Christmas Day.

They remained in there for several weeks before continuing on to Boston, where abolitionists hailed them as the heroes they were. They spent the next few months on a speaking tour of Massachusetts and then began boarding in the Beacon Hill home of black activist Lewis Hayden. Ellen worked as a seamstress and William as a cabinetmaker. He became both a successful tradesman and a leader in Boston’s black community.

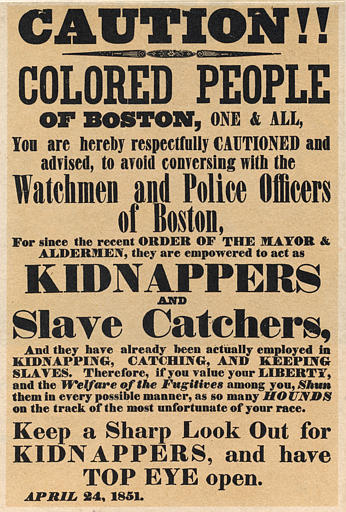

In September of 1850, however, a newly passed federal law, theFugitive Slave Act, put them in jeopardy. Northerners were now obliged to help slave owners reclaim their “property.” Within a month, two agents arrived in Boston looking for the Crafts. William barricaded himself in his shop while friends stood guard outside. The agents persisted, but William managed to get himself back to the Haydens’. Lewis Hayden armed his house with kegs of gunpowder and vowed to blow it up rather than surrender a single person under his protection. Ellen Craft went into hiding at Reverend Theodore Parker’s home. For the next two weeks, the minister wrote his sermons “with a sword in the open drawer under [his inkstand], and a pistol in the flap of the desk.”

Anti-slavery activists harassed and threatened the agents and followed them everywhere. In the course of five days, they had them arrested five different times on charges such as slander and attempted kidnapping. Finally, the agents were intimidated into leaving the city.

The abolitionists were jubilant, but they knew that the Crafts were no longer safe, even in Boston. When the Crafts’ former masters wrote to President Millard Fillmore for help, he replied that he would mobilize troops if necessary to see the law enforced. The Crafts decided that, like hundreds of other fugitive slaves, they would have to leave Boston. Since all the ports were being watched and guarded, they traveled overland to Nova Scotia, where they eventually boarded a boat to England.

The Crafts lived in England for the next 17 years. They educated themselves, raised five children, and worked on behalf of abolition. After the Civil War, the family returned to the United States, where William and Ellen founded a school for freed slaves in their native Georgia.

The Crafts’ story provided abolitionists like Theodore Parker with a dramatic example of why Bostonians should defy the Fugitive Slave Act. But southerners — and the federal government — were determined to enforce the law and return fugitive slaves to their owners. Like other radical abolitionists, Parker urged civil disobedience — to the point of violence if necessary — as a means of securing the freedom of slaves being sheltered in the North. When his case came before the court in April of 1855, all of Boston knew he would turn the trial into a debate on the morality of the Fugitive Slave Act. Reluctant to embroil himself in such an unpopular issue, the judge dismissed the case on a technicality, and Parker went free.

From the MassHumanities Mass Moments series.

<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Ellen and William Craft (top) and Ellen Craft in disguise.

‘Zdes’ pokoitsja telo/ negritjanki Kalimy/ vo Sv. Kresenii/ Nadezdy/ privezennoj vo Florenciju iz Nubii/ v 1827 godu . . . 1851// Primi mja Gospodi/ vo Carstvie Tvoe’/Qui giacciono le spoglie mortali della nera Kalima, nel Santo/ Battesimo chiamata Nadezda (Speranza) che è stata portata a Firenze dalla Nubia nel 1827 . . 1851, Accoglila Signore nel Tuo Regno/

Inscription in cyrillic on the tomb of Nadezhda, a Nubian girl brought to Florence at age 14 as a slave and baptized into the Russian Orthodox church.

A view of the Duomo from the English Cemetery