Long winter; overcast day. Take a walk through this view from the villa where I stayed last October.

Wonderful photo by Nancy Austin.

Long winter; overcast day. Take a walk through this view from the villa where I stayed last October.

Wonderful photo by Nancy Austin.

Posted in Florence

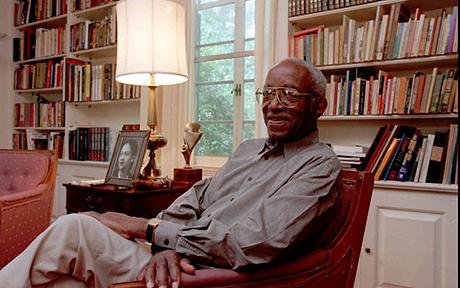

Professor John Hope Franklin, who died on March 25 aged 94, was a leading scholar of black American history and was among those who blazed a trail for generations of black academics.

Professor John Hope Franklin, who died on March 25 aged 94, was a leading scholar of black American history and was among those who blazed a trail for generations of black academics.

Dr. Franklin was also a world famous expert on the cultivation of orchids with a plant named after him. The yellow blossom above is named for his wife, Aurelia.

Posted in John Hope Franklin

Way past time for a Marion Brown revival – – or for an initial discovery for those who don’t yet know this sublime musician. Cover photo on Geechee Recollections was taken on my front porch at the time, in that very Geechee spot, Lakeview Avenue in Cambridge, MA.

I spoke with Marion on the phone about a year ago – – frail in body, but powerful and creative in mind and spirit.

Posted in Marion Brown

Two paintings by my late friend Garland Eliason-French. I wish I could show them to better advantage; the originals are actually quite large – – around 40″ x 60″ acrylic on canvas.

Posted in Garland Eliason

The sooner he becomes widely known, the more people will be delighted by his beautiful, profound, imaginative and unforgettable work. http://armelgaulme.blogspot.com

Posted in Armel Gaulme

This is a very disturbing article from the Providence Journal. Although Brown University is first quoted as committed to preserving the historic building which was the home of the major 19th-century African American painter Edward Mitchell Bannister, a later paragraph indicates their desire to pass off the building to an organization that clearly cannot afford to purchase or restore it.

Black contributions kept alive

Sunday, March 1, 2009

By NEIL DOWNING

Journal Staff Writer

Cows in Meadow by celebrated African-American artist Edward Bannister.

PROVIDENCE — One of the nation’s most celebrated African-American artists, Edward M. Bannister, gained prominencewhile living and working in Providence.

He won a national award for his work, at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876. He helped establish an organization that became the Providence Art Club. A gallery at Rhode Island College is named in his honor.

But the house in which he lived, at 93 Benevolent St. in the city’s College Hill section, is a decrepit, boarded-up brick building, owned by Brown University — and used by Brown to store refrigerators.

That is one of the points that emerged during a tour yesterday sponsored by the Rhode Island Historical Society, held in commemoration of Black History Month, and intended to celebrate the history of African Americans who lived on College Hill from 1701 to the present.

The tour was conducted by Ray Rickman, an African-American author, historian and former state representative. “The history of the African-American community is totally interwoven with College Hill, and that fact isn’t well-known,” Rickman said in an interview.

Along the two-hour tour, Rickman pointed out the former residences of prominent Providence people — including John Brown — who once made fortunes through the slave trade, amassing wealth and influence. “Let’s not lie to ourselves about our legacy,” Rickman said.

Rickman relayed the College Hill connections of such well-known African-American figures as Sissieretta Jones, an internationally acclaimed opera singer, and William J. Brown, whose autobiography recounts his days as a slave.

At one point in the tour, the bus paused outside a beaten-down structure with a board across its front door, a rusted gate outside, and an orange peel abandoned on its stone steps.

It was here, Rickman said, that Bannister, the renowned artist, lived with his wife, Christiana. But the building is one of several residences in the area that Brown University has boarded up and uses solely for storage — the Bannister house for refrigerators, Rickman said.

The Providence Preservation Society has included the building on its “most endangered properties” list.

Rickman acknowledged the many contributions that Brown University has made to the city and the state. But he said he wished that it would take steps to better care for the structure and formally recognize its historical significance.

Rickman said he has been assured by Brown University President Ruth J. Simmons — the first African-American to head an Ivy League university — that the building will be preserved. But he said that Brown should “treat it with respect” in the meantime. The Bannister house “should be a tourist attraction,” he said.

(University spokeswoman Marisa Quinn said yesterday: “Brown recognizes that it is an important historical building, and that’s why we’ve offered it” to the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society. If the society can raise the necessary funds to move the building, “It’s theirs,” she said.)

About 45 people took part in yesterday’s tour, said Barbara Barnes, tourism services manager for the Rhode Island Historical Society. They included Mildred Nichols of Providence, who came “because I have an enormous interest in African-American history, black history, and I know Ray Rickman is a scholar,” she said.

Bernard P. Fishman, the Rhode Island Historical Society’s executive director, said that interest in the tour was sparked by a number of factors, including the election of the nation’s first African-American president, a rekindled interest in Abraham Lincoln, Black History Month, and Rickman’s reputation as an authority on Rhode Island’s ties to the slave trade and knowledge about the state’s black community.

Edward Mitchell Bannister and Christiana Carteaux Bannister lived in this Providence, RI, house from 1884 until 1898.

……………………………..

Here Is The Statement I Made At A June 24, 2009 Meeting

On Behalf Of Saving Bannister’s House

Edward Mitchell Bannister Lived at 93 Benevolent Street

You sit here now. The house where your family lived when you were born has been torn down. The house you grew up in has been torn down; the first place you lived after college has been torn down; the place you lived in when you first married has been torn down. We shall all live to be at least 100 years old, but ten years after we die, the home we last inhabited will be torn down.

You are many things – character and personality and the sum of all you beheld, the influence of all who nurtured you. But can you really tell me that there is not a dimension of who you are that is defined by a sense of place? Every one of us can recite the addresses of homes in which we have lived – – maybe even the phone numbers.

Those tricks of memory are connected to the human regard for a sense of place. In the arts, Rembrandt’s very name, van Rijn, locates him in a place, as was the custom of that day. We go to the homes and studios, to stand in the place, to be within the walls, to see what Vermeer or Picasso saw, to see where Monet worked. We go to Giverny to see the gardens he created and painted, to see the kitchen table where he took his coffee. In this country we go to Chesterwood, to Cornish, New Hampshire, to Olana, for many reasons, among them because those are places where, in the arts, greatness dwelt. And we enjoy there a sense of connection to and indeed a deeper understanding of the lives and inspiration and work of the artists who inhabited those spaces.

Why does Edward Bannister deserve less? Why do we as a nation, or Providence as a city, deprive ourselves of the opportunity to claim this man’s greatness in a way that is not abstract and ephemeral? Edward Mitchell Bannister was a great man, an important man, a man of extraordinary talent, ability and achievement. And beyond that he was married to Christiana Carteaux, a woman of uncommon talent, accomplishment and purpose in her own right. They spent 14 years — fourteen of their most productive years, living at 93 Benevolent Street. He kept a studio elsewhere, but Edward Bannister lived, and thought, and sketched, and entertained, and daydreamed, and argued, and planned, and slept with his wife, or not – – they had a complex relationship, and straightened the pictures on the walls, and chatted with neighbors, in that house.

Across the street from Bannister’s home, and a block away at 110 Benevolent Street, Senator Nelson Aldrich lived. The desk is there in that building at which he drafted the Federal Reserve Act. That affects all of our lives today. And a big sign hangs outside that house proclaiming it the Rhode Island Historical Society at the Aldrich House.

At 93 Benevolent Street Edward Bannister rose up in the morning, walked though the rooms of his home, sat in the evenings and thought long and hard about Sabin Point, Narragansett Bay, and The Mill in Knightsville and Leucothea Rescuing Ulysses, and about A Man on Horseback And A Woman on Foot Driving Cattle. He thought about Oxen Hauling Rails, and Fort Dumpling at Jamestown, and a Street Scene in downtown Boston. And he made notes and drew sketches and thought about color and pigment and brushstroke and history and human interaction; about the beauty of the beasts of burden, the power and mystery of their presence in our world, and he thought about the people and the faces he set out to paint, about what they showed of lives lived and about how those lives can be enshrined on canvas.

African American art history is a kaleidoscope. Brilliant light, colors, visions swirling around, and there is an abundance of greatness there. We ooh and ahh, we celebrate, but we are not yet at the point of sustained close analysis of much of the work, its history, the very brushstrokes, the lives, the influences and conversations of most black American artists. We do not yet have the deep research, the catalogues raisonnee; the published presentations of bodies of work that establish stature beyond dispute; all the things that place an artist securely in the national and international canon, matters of race and gender aside. We are not there in part because as a nation we have yet to grasp the significance of the fullness of those lives, their histories, their careers including the meaning and cultural value of where they lived, where they worked.

One man on Benevolent Street wrote on paper and did many other things, fine and otherwise, always human, often political, that left him financially well off and garnered respect. Another man, a block away, drew on paper, painted on paper and on canvas, built a career that left him financially comfortable and made it possible for him to live his life as an artist. And he left a legacy to this nation as well. One that we understand less well than that of the politician Nelson Aldrich because the papers have not been gathered, the essays and books have yet to be written. Edward Bannister’s house has not been honored as a site where greatness dwelt and where inspiration remains in the shadows and the cobwebs and the crumbling walls and ceilings and floors.

These are bad times financially. And so the challenge is even greater. The challenge is to ask ourselves why, of those two houses, one should stand and the other should deteriorate? And depending upon your answer to that question, what are you going to do about it?

Posted in 19th century, Brown University, E.M.Bannister